This is the final section of a three part interview with Dr. Noel Fallows. You can read the previous sections in:

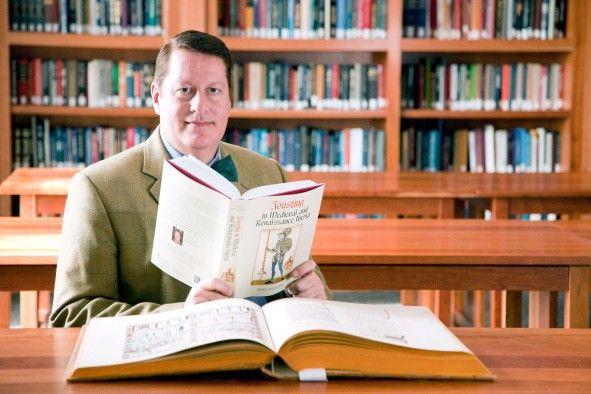

Dr. Fallows has a Ph.D. in Spanish from the University of Michigan and has been a faculty member at the University of Georgia since 1992. He served as the Acting Head of the Department of Romance Languages from 1998-2000 and served as the permanent Head from 2000-2007. He is currently the Associate Dean of International and Multidisciplinary Programs in the University's Franklin College of Arts and Sciences. His teaching and research interests focus primarily on the medieval and early modern periods. An interview with Dr. Fallows about his research into historical jousting was recently featured in the UGA Research magazine, which is quite an accomplishment since that magazine rarely includes articles about research in the humanities.

This interview has focused primarily on his book Jousting in Medieval and Renaissance Iberia, which serves not only as an academic text book, but also as the most comprehensive source of information on historical jousting for those involved in contemporary jousting.

The interview continues:

Regarding Historic Manuscripts and sources

Throughout your book, you include a number of excerpts (translated into English) of the Libro de la Orden de la Banda (Book of the Order of the Band) relating to the rules of the tourney and of the joust. The complete text has never been translated into English. Have you considered creating a complete English translation of this manuscript for publication? Or do you know of anyone who is working on a translation?

Well, truth be told, I completed a translation of this entire text a few years ago. I need to write an introduction and submit it somewhere for publication. The textual tradition of the manuscripts of this text is mind-bogglingly complex, and needs to be taken into account for this particular study. The best modern edition in Spanish was published in 1993, and this is the one I have used for my translation.

In footnote 22 on page 36 – 37, you mention that “The German tournament books constitute a unique and largely unexplored genre.” Do you know of anyone who is working on translating and publishing these German tournament books?

My latest catalogue from Brepols indicates that Helmut Nickel’s The Nuremberg Tournament Book is due out in 2015.

Have you considered working with these German texts to create a book on jousting in medieval and renaissance Germany?

I don’t know enough German, and even my book on the Spanish and Catalan texts, with which I have a deep familiarity, took me around 15 years to complete.

What is your opinion of the different styles of jousting in the 16th - 17th century Nuremberg Turnierbuch as described in “A Book of Tournaments and Parades From Nuremberg” by Helmut Nickel and Dirk H. Breiding? (in Metropolitan Museum Journal, v.45, 2010)

No strong opinion about this, except to say that it reflects the fact that jousting was never as simple and straightforward as has been thought. The armours reflect this as much as the texts.

In your book and also in the interview that is posted on the Boydell & Brewer website, you talk about how,”It is not widely known that the best jousters were able not only to wield the lance, but also the pen, in order to lampoon their competitors through the medium of poetry. These poems were circulated at the tournaments.” Do any of these poems survive? If so, where can they be seen? If they are not published anywhere that the public can view them, have you considered publishing them in some form?

See my answer above. These would be tricky to translate, as they are all based on puns and in-jokes, and are often difficult to decipher in the original. The Spanish ones have all been edited really well, with copious explanatory notes, in the following book:

Ian Macpherson. The “Invenciones y Letras” of the “Cancionero General". Papers of the Medieval Hispanic Research Seminar, vol. IX. London: Department of Hispanic Studies Queen Mary and Westfield College, 1998.

[To find a copy in your nearest library, use the WorldCat website.]

In discussing Don Luis Zapata de Chaves' manuscript, Miscelanea, o Varia Historia, you describe it as,”an eclectic compendium of anecdotes and personal memories, all of which, according to the author, are absolutely true.”(p. 57) You also spend the first chapter of your book establishing the credentials of the writers whose work you have translated. With modern texts, people are generally aware that just because something has been written down does NOT make it true. Yet among the general public, there still tends to be a belief that any historical document must, by virtue of its age, be accurate. What is your opinion of the general accuracy of historical documents that describe jousting?

You need to read chronicles and works of fiction with a degree of caution. The technical manuals are better sources of information because the authors were trying their best to be as accurate as possible. Quijada de Reayo’s book is actually a primer for his patron’s son, so he had every reason to be as practical as possible. In Zapata’s case, some of the anecdotes in the Micelánea are gossipy, but he is always deadly serious when it comes to jousting, as his knowledge of this subject was first-hand.

Can you provide examples of historical documents that you believe to be inaccurate in one way or another?

Treat chronicles with some caution – it is imperative to compare as many accounts as possible.

Along similar lines, what is your opinion of the general accuracy of historical drawings and paintings of the joust?

Some are better than others, depending on the skill of the draftsman. For the most part, the examples in my book are remarkably accurate, but there were so many jousts being staged throughout the Middle Ages and the Renaissance that it would have been fairly easy for an artist at the time to get a sense of what they looked like.

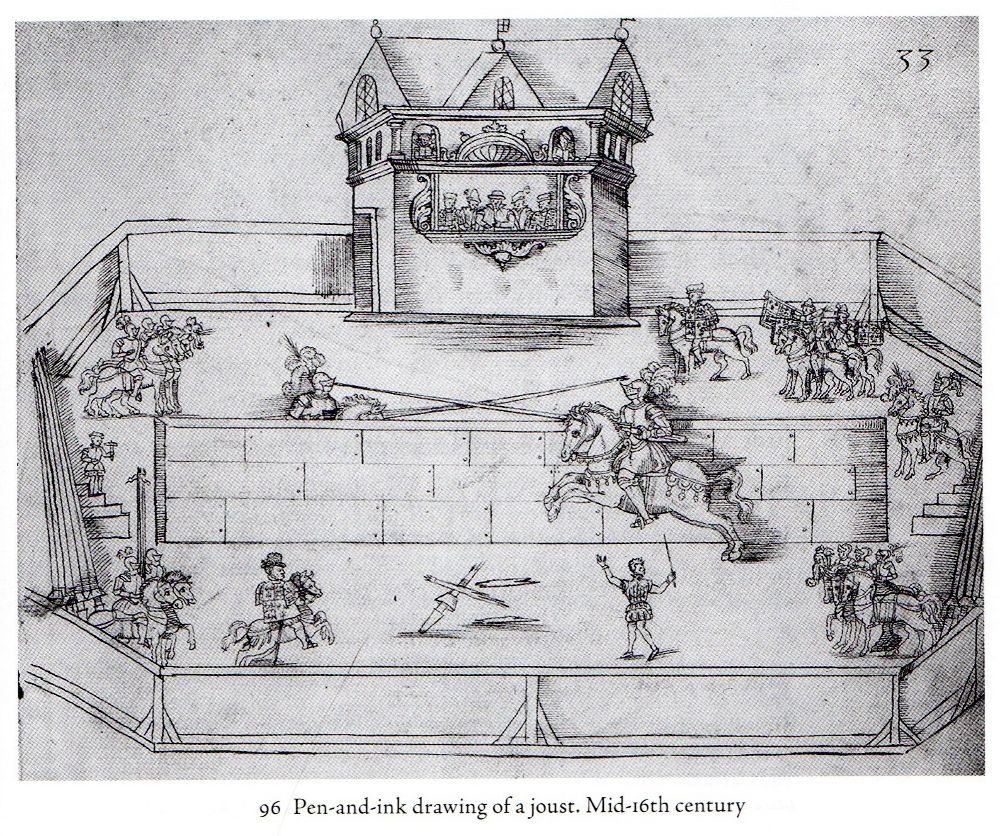

Possibly based on drawings such as figure 96 on the bottom of page 147,...

...there is a belief among many contemporary jousters that the Italians jousted right shoulder to right shoulder. Do you believe that any group actually jousted that way?

I have to say, No. I think that if holding a pen in the left hand was frowned upon back then, the same was probably true of a lance, and keep in mind that although I (foolishly, thinking back) did not include it in the book, there is another version of that exact same drawing in a manuscript in the British Library where the jousters have been repositioned correctly, left arm to left arm. Don Luis Zapata was a master of the Italian style and he is very forceful on the issue of jousting left arm to left arm. He surely would have let us know if there were exceptions to this fundamental issue.

Various arguments have been presented by other scholars that jousting tournaments were a way of training for war. However, you disagree. “Within the general context of the tournament, and specifically in the case of the joust, the texts discussed in this volume confirm that this activity was an end unto itself...” (p. 240) Do you mean to state that jousting competitions, even in their earliest forms, were never in any way related to training for war?

They were callisthenic, and promoted technical virtuosity with the lance, and esprit de corps, but beyond that, I haven’t seen any concrete contemporary evidence that they were training exercises for a different chivalric activity: war. Certainly Zapata, the pacifist champion jouster, trained to be a jouster, without ever fighting in a war. Quijada de Reayo in his treatise makes a clear distinction between jousting and warfare, without specifying that one is training for the other.

In Conclusion

Would you like to actually put on armour, get on a horse and give jousting a try?

I do not want to try jousting; only write about it and comment on it. I would, however, love to don a complete armour! I could probably also come up with some witty poetry if pushed.

If so, which aspects of modern jousting tournaments would you most like to try? Mounted Skill at Arms? Mounted Melee? Actual jousting/tilting?

None of the above. I am content being a spectator and commentator. I realize that some re-enactors believe that you absolutely must practice jousting in order to be able to write about it, but the kind of work that I do is mostly sedentary (though still exhausting at times!) archival research. The aim of my book is to go far beyond the practicalities of jousting, e.g. I discuss the lives of three practicing champions, the controversial relationship between jousting and warfare, the historical evolution of arms and armour, the political and social implications of competing riding styles, the ethics of Chivalry, its paradoxes, contradictions and tensions, etc.

I am fortunate to have good friends that I can rely on if I need to know more about certain concrete, practical details, and to my mind there is no question that my book would have been of much lesser quality without their help. On the flip-side of this, most modern practitioners of the joust do not have years of experience finding previously lost or unknown medieval Spanish and Catalan manuscripts in archives, and then deciphering them, so the relationship is symbiotic. I would say that we need to rely on each other’s skill-sets in order to understand the overall complexities of the sport. That’s what makes us a true, diverse community of experts and enthusiasts.

If you, personally, had the capability of producing your ideal contemporary jousting tournament, what would it be like?

I would shoot for accuracy, with personal preference for sixteenth-century armours and pageantry and follow-up banquet.

What would you like to see happen with contemporary competitive jousting?

Long may it continue.

Are you currently working on a book or translation related to jousting that you would like to tell us something about?

In 2013 I published two new books, as follows: a translation of Ramon Llull’s Book of the Order of Chivalry (Woodbridge, Suffolk, UK, and Rochester, New York, USA: The Boydell Press, 2013); and another book called The Twelve of England. Deeds of Arms Series, Volume 3 (Wheaton, IL: Freelance Academy Press, 2013). These books will both be of interest to The Jousting Life community, I think. Full blurbs as to what they are about are at these web sites:

The Book of the Order of Chivalry

The Twelve of England

I also wrote a lengthy article for an exhibit catalogue: “Masters of Fear or Masters of Arms? Jerónimo de Carranza, Luis Pacheco de Narváez and the Martial Arts Treatises of Renaissance Spain.” In The Noble Art of the Sword: Fashion and Fencing in Renaissance Europe 1520-1630. Edited by Tobias Capwell. London, UK: The Wallace Collection, 2012. 219-235.

Currently I really need to finish the Order of the Band book, especially as I have finished the translation. I am also working on a monograph about the last public duel in Spain, which took place in Valladolid in 1522. I am working on these projects at a leisurely pace, having had a very intensive period of writing and publishing in 2013. And finally, I have been tinkering for some years now on a book about my hobby: a collector’s guide to British army militaria from the Victorian and Edwardian periods.

What's the most important thing you want to people to understand/remember after reading Jousting in Medieval and Renaissance Iberia?

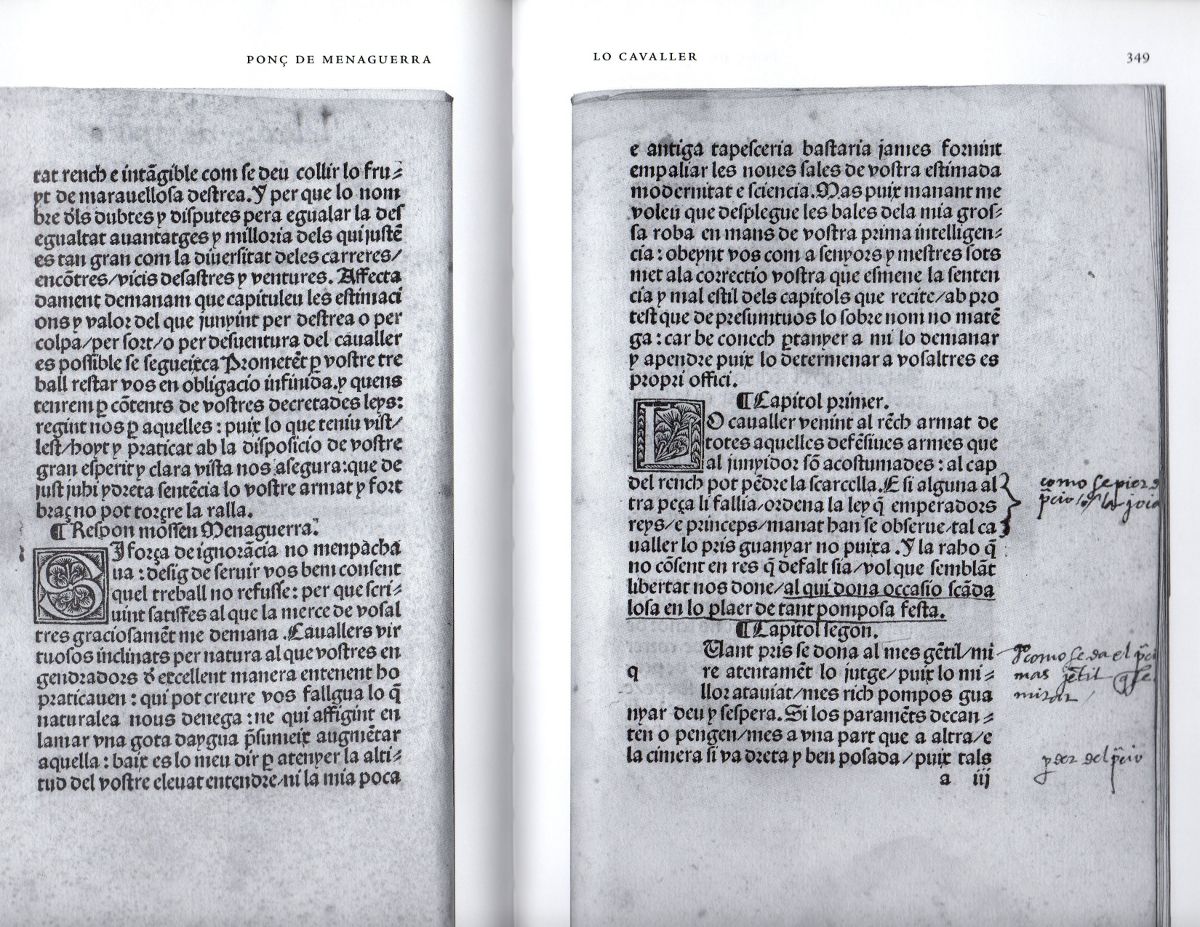

I say in the beginning of the book that Chivalry must be seen to be properly understood, so it’s important to me that the texts that I have studied and translated are always read alongside the images of arms, armour, effigies, manuscript illuminations, paintings, etc. For me, the history of Chivalry is as much a visual as a narrative history.

This interview began in:

"An Interview with Dr. Noel Fallows, Author of Jousting in Medieval and Renaissance Iberia: Part One"

and

"An Interview with Dr. Noel Fallows, Author of Jousting in Medieval and Renaissance Iberia: Part Two"

Related articles:

Video: Dr. Noel Fallows Talks About Chivalry and Jousting

Arundel Castle International Jousting Tournament 2013

There are also numerous articles about The Grand Tournament of Sankt Wendel

Dr. Fallows has a Ph.D. in Spanish from the University of Michigan and has been a faculty member at the University of Georgia since 1992. He served as the Acting Head of the Department of Romance Languages from 1998-2000 and served as the permanent Head from 2000-2007. He is currently the Associate Dean of International and Multidisciplinary Programs in the University's Franklin College of Arts and Sciences. His teaching and research interests focus primarily on the medieval and early modern periods. An interview with Dr. Fallows about his research into historical jousting was recently featured in the UGA Research magazine, which is quite an accomplishment since that magazine rarely includes articles about research in the humanities.

This interview has focused primarily on his book Jousting in Medieval and Renaissance Iberia, which serves not only as an academic text book, but also as the most comprehensive source of information on historical jousting for those involved in contemporary jousting.

The interview continues:

Regarding Historic Manuscripts and sources

Throughout your book, you include a number of excerpts (translated into English) of the Libro de la Orden de la Banda (Book of the Order of the Band) relating to the rules of the tourney and of the joust. The complete text has never been translated into English. Have you considered creating a complete English translation of this manuscript for publication? Or do you know of anyone who is working on a translation?

Well, truth be told, I completed a translation of this entire text a few years ago. I need to write an introduction and submit it somewhere for publication. The textual tradition of the manuscripts of this text is mind-bogglingly complex, and needs to be taken into account for this particular study. The best modern edition in Spanish was published in 1993, and this is the one I have used for my translation.

In footnote 22 on page 36 – 37, you mention that “The German tournament books constitute a unique and largely unexplored genre.” Do you know of anyone who is working on translating and publishing these German tournament books?

My latest catalogue from Brepols indicates that Helmut Nickel’s The Nuremberg Tournament Book is due out in 2015.

Have you considered working with these German texts to create a book on jousting in medieval and renaissance Germany?

I don’t know enough German, and even my book on the Spanish and Catalan texts, with which I have a deep familiarity, took me around 15 years to complete.

What is your opinion of the different styles of jousting in the 16th - 17th century Nuremberg Turnierbuch as described in “A Book of Tournaments and Parades From Nuremberg” by Helmut Nickel and Dirk H. Breiding? (in Metropolitan Museum Journal, v.45, 2010)

No strong opinion about this, except to say that it reflects the fact that jousting was never as simple and straightforward as has been thought. The armours reflect this as much as the texts.

In your book and also in the interview that is posted on the Boydell & Brewer website, you talk about how,”It is not widely known that the best jousters were able not only to wield the lance, but also the pen, in order to lampoon their competitors through the medium of poetry. These poems were circulated at the tournaments.” Do any of these poems survive? If so, where can they be seen? If they are not published anywhere that the public can view them, have you considered publishing them in some form?

See my answer above. These would be tricky to translate, as they are all based on puns and in-jokes, and are often difficult to decipher in the original. The Spanish ones have all been edited really well, with copious explanatory notes, in the following book:

Ian Macpherson. The “Invenciones y Letras” of the “Cancionero General". Papers of the Medieval Hispanic Research Seminar, vol. IX. London: Department of Hispanic Studies Queen Mary and Westfield College, 1998.

[To find a copy in your nearest library, use the WorldCat website.]

In discussing Don Luis Zapata de Chaves' manuscript, Miscelanea, o Varia Historia, you describe it as,”an eclectic compendium of anecdotes and personal memories, all of which, according to the author, are absolutely true.”(p. 57) You also spend the first chapter of your book establishing the credentials of the writers whose work you have translated. With modern texts, people are generally aware that just because something has been written down does NOT make it true. Yet among the general public, there still tends to be a belief that any historical document must, by virtue of its age, be accurate. What is your opinion of the general accuracy of historical documents that describe jousting?

You need to read chronicles and works of fiction with a degree of caution. The technical manuals are better sources of information because the authors were trying their best to be as accurate as possible. Quijada de Reayo’s book is actually a primer for his patron’s son, so he had every reason to be as practical as possible. In Zapata’s case, some of the anecdotes in the Micelánea are gossipy, but he is always deadly serious when it comes to jousting, as his knowledge of this subject was first-hand.

Can you provide examples of historical documents that you believe to be inaccurate in one way or another?

Treat chronicles with some caution – it is imperative to compare as many accounts as possible.

Along similar lines, what is your opinion of the general accuracy of historical drawings and paintings of the joust?

Some are better than others, depending on the skill of the draftsman. For the most part, the examples in my book are remarkably accurate, but there were so many jousts being staged throughout the Middle Ages and the Renaissance that it would have been fairly easy for an artist at the time to get a sense of what they looked like.

Possibly based on drawings such as figure 96 on the bottom of page 147,...

...there is a belief among many contemporary jousters that the Italians jousted right shoulder to right shoulder. Do you believe that any group actually jousted that way?

I have to say, No. I think that if holding a pen in the left hand was frowned upon back then, the same was probably true of a lance, and keep in mind that although I (foolishly, thinking back) did not include it in the book, there is another version of that exact same drawing in a manuscript in the British Library where the jousters have been repositioned correctly, left arm to left arm. Don Luis Zapata was a master of the Italian style and he is very forceful on the issue of jousting left arm to left arm. He surely would have let us know if there were exceptions to this fundamental issue.

Various arguments have been presented by other scholars that jousting tournaments were a way of training for war. However, you disagree. “Within the general context of the tournament, and specifically in the case of the joust, the texts discussed in this volume confirm that this activity was an end unto itself...” (p. 240) Do you mean to state that jousting competitions, even in their earliest forms, were never in any way related to training for war?

They were callisthenic, and promoted technical virtuosity with the lance, and esprit de corps, but beyond that, I haven’t seen any concrete contemporary evidence that they were training exercises for a different chivalric activity: war. Certainly Zapata, the pacifist champion jouster, trained to be a jouster, without ever fighting in a war. Quijada de Reayo in his treatise makes a clear distinction between jousting and warfare, without specifying that one is training for the other.

In Conclusion

Would you like to actually put on armour, get on a horse and give jousting a try?

I do not want to try jousting; only write about it and comment on it. I would, however, love to don a complete armour! I could probably also come up with some witty poetry if pushed.

If so, which aspects of modern jousting tournaments would you most like to try? Mounted Skill at Arms? Mounted Melee? Actual jousting/tilting?

None of the above. I am content being a spectator and commentator. I realize that some re-enactors believe that you absolutely must practice jousting in order to be able to write about it, but the kind of work that I do is mostly sedentary (though still exhausting at times!) archival research. The aim of my book is to go far beyond the practicalities of jousting, e.g. I discuss the lives of three practicing champions, the controversial relationship between jousting and warfare, the historical evolution of arms and armour, the political and social implications of competing riding styles, the ethics of Chivalry, its paradoxes, contradictions and tensions, etc.

I am fortunate to have good friends that I can rely on if I need to know more about certain concrete, practical details, and to my mind there is no question that my book would have been of much lesser quality without their help. On the flip-side of this, most modern practitioners of the joust do not have years of experience finding previously lost or unknown medieval Spanish and Catalan manuscripts in archives, and then deciphering them, so the relationship is symbiotic. I would say that we need to rely on each other’s skill-sets in order to understand the overall complexities of the sport. That’s what makes us a true, diverse community of experts and enthusiasts.

If you, personally, had the capability of producing your ideal contemporary jousting tournament, what would it be like?

I would shoot for accuracy, with personal preference for sixteenth-century armours and pageantry and follow-up banquet.

What would you like to see happen with contemporary competitive jousting?

Long may it continue.

Are you currently working on a book or translation related to jousting that you would like to tell us something about?

In 2013 I published two new books, as follows: a translation of Ramon Llull’s Book of the Order of Chivalry (Woodbridge, Suffolk, UK, and Rochester, New York, USA: The Boydell Press, 2013); and another book called The Twelve of England. Deeds of Arms Series, Volume 3 (Wheaton, IL: Freelance Academy Press, 2013). These books will both be of interest to The Jousting Life community, I think. Full blurbs as to what they are about are at these web sites:

The Book of the Order of Chivalry

The Twelve of England

I also wrote a lengthy article for an exhibit catalogue: “Masters of Fear or Masters of Arms? Jerónimo de Carranza, Luis Pacheco de Narváez and the Martial Arts Treatises of Renaissance Spain.” In The Noble Art of the Sword: Fashion and Fencing in Renaissance Europe 1520-1630. Edited by Tobias Capwell. London, UK: The Wallace Collection, 2012. 219-235.

Currently I really need to finish the Order of the Band book, especially as I have finished the translation. I am also working on a monograph about the last public duel in Spain, which took place in Valladolid in 1522. I am working on these projects at a leisurely pace, having had a very intensive period of writing and publishing in 2013. And finally, I have been tinkering for some years now on a book about my hobby: a collector’s guide to British army militaria from the Victorian and Edwardian periods.

What's the most important thing you want to people to understand/remember after reading Jousting in Medieval and Renaissance Iberia?

I say in the beginning of the book that Chivalry must be seen to be properly understood, so it’s important to me that the texts that I have studied and translated are always read alongside the images of arms, armour, effigies, manuscript illuminations, paintings, etc. For me, the history of Chivalry is as much a visual as a narrative history.

This interview began in:

"An Interview with Dr. Noel Fallows, Author of Jousting in Medieval and Renaissance Iberia: Part One"

and

"An Interview with Dr. Noel Fallows, Author of Jousting in Medieval and Renaissance Iberia: Part Two"

Related articles:

Video: Dr. Noel Fallows Talks About Chivalry and Jousting

Arundel Castle International Jousting Tournament 2013

There are also numerous articles about The Grand Tournament of Sankt Wendel

No comments:

Post a Comment